I've been reading through the book of Job this month. This brought to mind a piece of music which I haven't heard since May 2013: Et misericordia, by Clare Maclean.

The book of Job made a deep impression on me when I first read it in 2011. I happened to be going through a pretty dark patch of my life at the time, so I felt some kind of solidarity with Job as he called upon God for answers. It's a pretty standard complaint: If God is good and omnipotent, why is there suffering and injustice in the world? I loved that the Bible wasn't shying away from those questions, and I looked forward to getting some answers...

When I got to the last few chapters, in which God responds to Job ("out of the whirlwind"), I was stunned. Instead of providing answers, God bombards Job with a long chain of his own questions:

The book of Job made a deep impression on me when I first read it in 2011. I happened to be going through a pretty dark patch of my life at the time, so I felt some kind of solidarity with Job as he called upon God for answers. It's a pretty standard complaint: If God is good and omnipotent, why is there suffering and injustice in the world? I loved that the Bible wasn't shying away from those questions, and I looked forward to getting some answers...

When I got to the last few chapters, in which God responds to Job ("out of the whirlwind"), I was stunned. Instead of providing answers, God bombards Job with a long chain of his own questions:

Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth?

Declare, if you have understanding.

Who determined its measurements, or who stretched the line upon it?

On what do its foundations rest, or who laid its corner stone,

When the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?

These are the words Clare Maclean starts with (from chapter 38 of Job). The music actually sounds confronting. The opening chords get more and more insistent as the thick, full-voiced harmonies pile up. God declares himself as the unfathomable, unreachable Creator through the awesome scope of the created universe, and we hear it all in the music. Earth, stars, light, darkness, wind and water – all are portrayed with a music that emphasises their mystery and complexity. (Maclean writes for 12-part chorus, often very contrapuntally, so it's not an easy piece.)

The word painting is exquisite. I love the scintillating depiction of “light diffused” and the thick, cloudy, misaligned chords of the sea “shut in with doors”. I'm struck by something new each time I listen. You can hear the composer's wonder at the created natural world in the sheer inventiveness of the music – just like with Haydn's brilliant Creation oratorio, which I listened to last week.

But how does all this awe and wonder answer the question of human suffering?

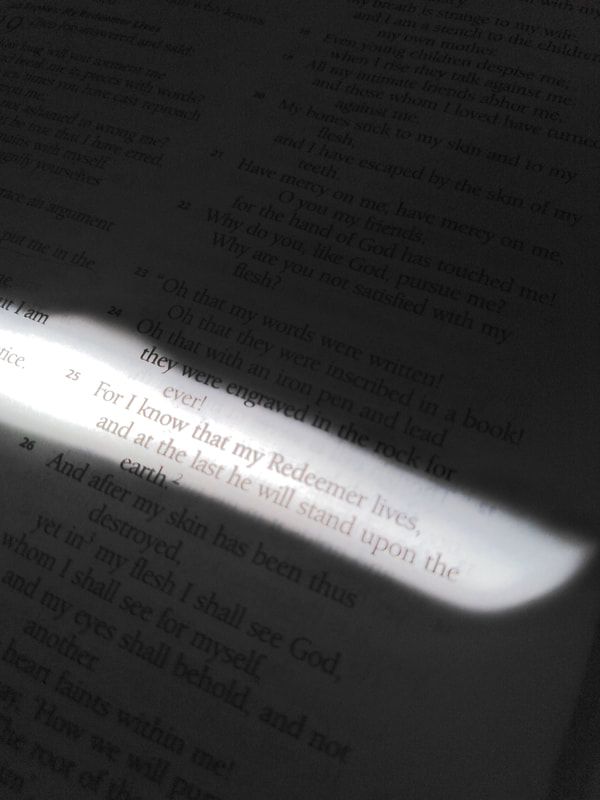

There is something more. Twice we hear words in Latin, taken from the Magnificat: Et misericordia eius a progenie in progenies timentibus eum (“And his mercy extends from generation to generation for those who fear him”). This is a signpost, pointing to the very heart of the work. And here, the overwhelming extravagance of creation is momentarily stilled – “the surface of the deep is frozen,” sings the choir, as the harmony falls in to a single note. And then, just for a moment, the misty counterpoint is cleared away, the foreign harmonies become familiar, and the divine becomes human. The gulf of the ‘unknown’ is bridged: “For I know that my Redeemer lives.”

The word painting is exquisite. I love the scintillating depiction of “light diffused” and the thick, cloudy, misaligned chords of the sea “shut in with doors”. I'm struck by something new each time I listen. You can hear the composer's wonder at the created natural world in the sheer inventiveness of the music – just like with Haydn's brilliant Creation oratorio, which I listened to last week.

But how does all this awe and wonder answer the question of human suffering?

There is something more. Twice we hear words in Latin, taken from the Magnificat: Et misericordia eius a progenie in progenies timentibus eum (“And his mercy extends from generation to generation for those who fear him”). This is a signpost, pointing to the very heart of the work. And here, the overwhelming extravagance of creation is momentarily stilled – “the surface of the deep is frozen,” sings the choir, as the harmony falls in to a single note. And then, just for a moment, the misty counterpoint is cleared away, the foreign harmonies become familiar, and the divine becomes human. The gulf of the ‘unknown’ is bridged: “For I know that my Redeemer lives.”

This text comes from earlier in Job (19:25), a fragment of light and hope in the middle of one of his many impassioned speeches. By placing it here, in the middle of God's speech of chapter 38, and signposted with a quote from the Magnificat, Clare Maclean points to Jesus Christ as Job's longed-for Redeemer.

I love how Clare Maclean has chosen and structured these texts, and then how she's set them to music. The main body of the piece, with text from Job 38, shows God's glory in all its vastness and grandeur, and it's frankly terrifying – he really has made everything. The title and the quote from the Magnificat (Luke 1:50) points us to God's mercy, and our humility before him ("His mercy is for those who fear him"). And at the heart of the work is God's love, in the promise of the Redeemer.

There's way too much depth here for a single blog post. But hopefully I've shown something about how I think this work glorifies God.

Unfortunately for my readers, there doesn't seem to be a readily available recording online. But if you're really inspired to seek it out, you can buy an MP3 recording from the Sydney Chamber Choir here, or find it on one of the Adelaide Chamber Singers' CDs here.

I love how Clare Maclean has chosen and structured these texts, and then how she's set them to music. The main body of the piece, with text from Job 38, shows God's glory in all its vastness and grandeur, and it's frankly terrifying – he really has made everything. The title and the quote from the Magnificat (Luke 1:50) points us to God's mercy, and our humility before him ("His mercy is for those who fear him"). And at the heart of the work is God's love, in the promise of the Redeemer.

There's way too much depth here for a single blog post. But hopefully I've shown something about how I think this work glorifies God.

Unfortunately for my readers, there doesn't seem to be a readily available recording online. But if you're really inspired to seek it out, you can buy an MP3 recording from the Sydney Chamber Choir here, or find it on one of the Adelaide Chamber Singers' CDs here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed